13 Transformations

We will talk in the class (or read here! https://online.stat.psu.edu/stat501/lesson/9 ) about why to apply transformations. Here I will simply show you how.

We simply make a new column and use maths to fill in the value.

For example. Here is some data.

## x y

## 1 10.2564 16.4663

## 2 3.0769 4.9279

## 3 15.1282 26.4663

## 4 27.4359 30.3125

## 5 12.0513 13.7740

## 6 23.0769 13.7740To make a column with \(\frac{1}{x}\) as the predictor, I would use the $ to create a new column a and on the other side of the arrow, take the fraction.

# Note I am trying to avoid spaces or special characters in my data

data$transform_1overx <- 1/data$xTo make a column with \(x^2\) as the predictor, we do

# Note I am trying to avoid spaces or special characters in my data

data$transform_xsquare <- data$x^2To make a column with \(\log(x)\) as the predictor, we do (this is the NATURAL LOG)

# Note I am trying to avoid spaces or special characters in my data

data$transform_lnx <- log(data$x)To make a column with \(\log_{10}(x)\) as the predictor, we do

# Note I am trying to avoid spaces or special characters in my data

data$transform_logx <- log(data$x,base=10)To make a column with \(\sqrt{x}\) as the predictor, we do

# Note I am trying to avoid spaces or special characters in my data

data$transform_sqrtx <- sqrt(data$x)And let’s see the output

head(data)## x y transform_1overx transform_xsquare transform_lnx

## 1 10.2564 16.4663 0.09750010 105.193741 2.327902

## 2 3.0769 4.9279 0.32500244 9.467314 1.123923

## 3 15.1282 26.4663 0.06610172 228.862435 2.716561

## 4 27.4359 30.3125 0.03644859 752.728609 3.311852

## 5 12.0513 13.7740 0.08297860 145.233832 2.489173

## 6 23.0769 13.7740 0.04333338 532.543314 3.138832

## transform_logx transform_sqrtx

## 1 1.0109950 3.202561

## 2 0.4881134 1.754109

## 3 1.1797873 3.889499

## 4 1.4383192 5.237929

## 5 1.0810339 3.471498

## 6 1.3631775 4.803842We could now perform our linear regression with any of these as our predictor. For example

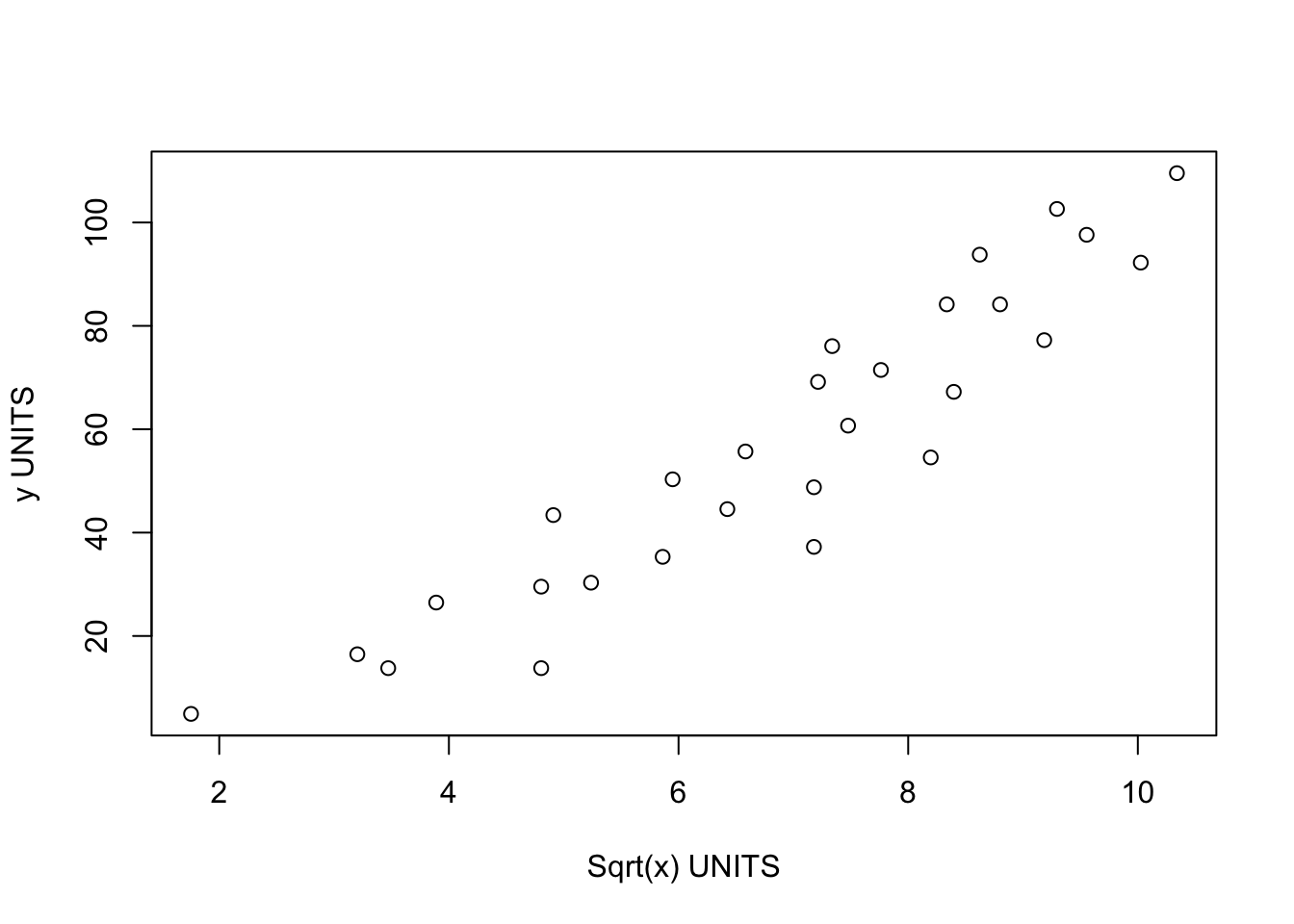

newmodel <- lm(y~transform_sqrtx,data=data)

plot(data$y~data$transform_sqrtx,xlab="Sqrt(x) UNITS",ylab="y UNITS")

You don’t have to make a new column in advance, you can do the maths within the regression itself:

newmodel2 <- lm(y~sqrt(x),data=data)

# For Polynomial regression you can use the poly command e.g. X+X^2

newmodel3 <- lm(y ~ poly(x,2),data=data)

summary(newmodel3)##

## Call:

## lm(formula = y ~ poly(x, 2), data = data)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -20.945 -6.344 1.280 6.887 15.652

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 56.823 1.936 29.352 < 2e-16 ***

## poly(x, 2)1 144.687 10.244 14.124 2.03e-13 ***

## poly(x, 2)2 -7.937 10.244 -0.775 0.446

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 10.24 on 25 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.8889, Adjusted R-squared: 0.8801

## F-statistic: 100 on 2 and 25 DF, p-value: 1.174e-12

equatiomatic::extract_eq(newmodel3)\[ \operatorname{y} = \alpha + \beta_{1}(\operatorname{x}) + \beta_{2}(\operatorname{x^2}) + \epsilon \]